collection Keramisch Museum Goedewaagen

Spring is in the air ...

Stagnation in design continued until the early Fifties. By then, the economy had picked up again and customers had more money to spend. The dark days were over and people wanted to enjoy themselves. Pre-war commodity earthenwares were discarded and, led by consumer organisations such as Goed Wonen (Living Well), consumers chose practical, light-weight, stackable china - preferably in cheerful, light colours to express their sense of a new era. But while consumers had more to spend, supply increased too. The market was flooded with imports that were not only much cheaper but made of better materials. Dirt-cheap porcelain was imported from Eastern Europe. Even the luxury wares of the major German brands were found to be affordable in comparison with Dutch earthenwares.Competition

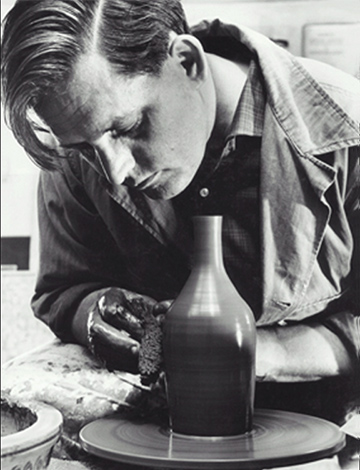

Dutch manufacturers quickly realized that in order to survive in this competitive environment their first objective must be to improve the quality of their products. Goedewaagen, too, tried to find an alternative for its vulnerable lime pottery. After much experimenting, stoneware was developed, a much harder material that does not absorb water. The disadvantage was that stoneware undergoes significant shrinkage during baking, more than earthenware. The company’s old moulds could no longer be used so for part of the collection new moulds were made. But Goedewaagen also realized that new models were of the essence. To this end new designers were needed. Among these, Zweitse Landsheer became prominent.

Photo: Bonnie Loef

(between 1953 and '59)

courtesy Keramisch Museum Gouda

Having studied with Willem de Vries at the Instituut voor Kunstnijverheidsonderwijs (Institute for Applied Arts Training) in Amsterdam and conscious of his social responsibility, Landsheer applied for a position at the earthenware manufacturers. Goedewaagen were willing to hire him, but not as a designer. They made him a clay porter. A year and a half later, in 1953, he was allowed to create his first design: a condiments set for pepper, salt and mustard. His design is a play on two basic forms that were typical of the Fifties, the oval and the kidney. It was immediately accepted as his masterpiece and Landsheer was hired as designer.

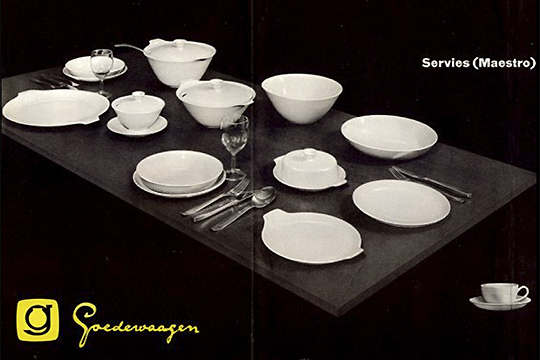

Maestro

Zweitse Landsheer designed his first complete china set in 1955. It was marketed in 1956. Called Maestro and fitted with surprising knobs on the lids, it became a great commercial success. And it was relatively simple to manufacture as well. Some influence of Floris Meydam’s Black Princess (1955) may be detected here, certainly for the milk jugs. Because of the use of a new material, based on English feldspar, this Goedewaagen service was of better quality than previous products. Maestro was chosen to represent the Dutch earthenware industry on the Milan Triennial Exhibition, together with works by Willem de Vries (of the Fris company) and Edmond Bellefroid (Mosa).

Special issue service Jamboree:

breakfast service 1025

(1939) with the Scouting decoration (1945).

The first new set made after WW II.

Collection K.M.G.

photo courtesy K.M.G.

Royal Goedewaagen

Van Breukelen versus Bellefroid

During the second World War the Dutch china and earthenware manufacturing largely came to a standstill. The occupying forces did not allow production, there were no customers to buy china, and the factories lacked raw materials and staff. For many of their staff had been pressed into service in arms factories in Germany. And of such products as were made, manufacturers were obliged to export most to Germany, to make up for shortages there. In the war’s last year production stopped completely, largely because of a lack of raw materials and especially fuel.

Once the war was over

In the period directly after World War II there was no innovation to speak of. It was hard enough to get factories started up again. And there was such a shortage of dinnerware that customers seemed not to care about design. From a financial point of view Goedewaagen would have preferred to spend its time and resources on decorative earthenwares, since more money could be made doing so. But the government prevented this. Earthenware production was tightly regulated and raw material shortages provoked extra taxes on luxury products.

Goedewaagen

page 3